- Home

- Melanie Hobson

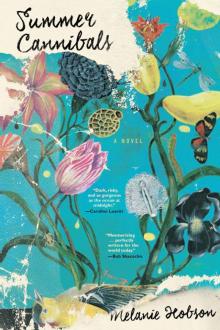

Summer Cannibals

Summer Cannibals Read online

Praise for

Summer Cannibals

“Melanie Hobson writes with the dark energy and twisted exuberance reminiscent of her most celebrated predecessors—Atwood, Murdoch, Oates, and so many others plumbing the raw, violent depths of toxic families. Her mesmerizing characters are semi-feral, trapped and struggling under the terrible weight of what a man can do to a girl, a daughter, a wife. Summer Cannibals seems perfectly written for the world today, our blind greedy stumble from thing to thing.”

—Bob Shacochis, author of The Woman Who Lost Her Soul

“Dark, risky, and as gorgeous as the ocean at midnight, Hobson’s exquisitely written debut gathers a fractured grown family together for six dangerous days of lust, longing, sex, secrets, and stunning betrayals. The story may be set in the languid days of summer, but My God, it’s a terrific scorcher.”

—Caroline Leavitt, author of Is This Tomorrow

“There is a quality to Melanie Hobson’s writing that reminds me of Brideshead Revisited or certain John Cheever stories; a quality of languid lyricism and moral corruption that I found immediately arresting. The story of three sisters carrying out both subtle and shocking acts of deceit and desire (And oh, Pippa!) is something to be savored like a gin and tonic on a summer afternoon by the lake. But a storm is rolling in and the water, moments ago so inviting and glorious, begins to grow dark. Is it safe? Should you dive in? Summer Cannibals announces the arrival of a great talent that book clubs and reviewers alike will adore.”

—Matt Bondurant, author of The Night Swimmer

“Summer Cannibals is a story of domestic mayhem, where hidden angers spur tensions that manifest in the most unlikely ways. I was on the edge of my seat until the very end when, with the force of a tsunami, everything that’s been built comes crashing down, to devastating effect.” —Yasuko Thanh, author of Mysterious Fragrance of the Yellow Mountains

“An elegant, sexy story of four scarred but undaunted women and one seriously monstrous patriarch, Summer Cannibals simmers languidly up to an explosive finale which reminds us, in an unforgettable manner, that no institution in our lives is more powerful or perilous than our families. Melanie Hobson’s indelible voice somehow conveys both boundless compassion for human frailty and wit as lethal as a straight razor held at the base of the throat. Family dysfunction at its finest.”

—Ed Tarkington, author of Only Love Can Break Your Heart

Summer

Cannibals

Melanie Hobson

Copyright © 2018 by Melanie Hobson

Cover design by Terri Nimmo

Cover Artwork © Olaf Hajek

Background pattern © Cafe Racer/Shutterstock

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. Scanning, uploading, and electronic distribution of this book or the facilitation of such without the permission of the publisher is prohibited. Please purchase only authorized electronic editions, and do not participate in or encourage electronic piracy of copyrighted materials. Your support of the author’s rights is appreciated. Any member of educational institutions wishing to photocopy part or all of the work for classroom use, or anthology, should send inquiries to Grove Atlantic, 154 West 14th Street, New York, NY 10011 or [email protected].

First published in Canada in 2018 by Penguin Random House

First Grove Atlantic edition: September 2018

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN 978-0-8021-2852-2

eISBN 978-0-8021-4652-6

Black Cat

an imprint of Grove Atlantic

154 West 14th Street

New York, NY 10011

Distributed by Publishers Group West

groveatlantic.com

18 19 20 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

For Charlie,

Aidan & Phoebe.

And for my sisters:

Helen, Megan, Imogen, Elizabeth, Fleur.

Table of Contents

Cover

Praise for Summer Cannibals

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Thursday

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Friday

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Saturday

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Sunday

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Monday

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Tuesday

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Epilogue

Acknowledgements

Back Cover

Thursday

1

The house had its way of holding them. Their father liked to tell how he’d bought it with a credit card—a cash advance to make up the ten percent needed for the deposit—and it seemed as equally and gloriously ridiculous, that this should all be theirs. That first day, after the papers were signed, the sisters had run laughing and shrieking through the house with its three floors, two staircases, seven bedrooms and all the rest—living, dining, family, library, kitchen, butler’s pantry, bathrooms, hallways, passageways and entryways. They explored and claimed rooms and then just as quickly relinquished them as they found another and another, shouting that they were lost, crying out that they’d found “the best thing ever,” bare feet thudding up and down, up and down, across and over. Doors slammed. Drawers were pulled open and locks fiddled with. The old laundry chute was discovered and heads were put through the small doors on each landing that let into it as they prodded each other, but none of them were brave enough to go to the chute’s terminus in the basement. That rough stone-walled basement the original builders had dynamited from the solid limestone of the escarpment the house was perched on. Beyond the house’s walls, at the base of that cliff, was the city—gridded to the enormous lake like a mesh to keep the jutting land, and all it supported, from tumbling down.

I can’t hear the children, their father had said, looking at his wife triumphantly. This house swallows them.

They were leaning on the metal fence at the cliff’s edge, the whole world spread out in front of them, and anyone would think these parents too young to have all this. That something was wrong; a mistake. But they knew that this was nothing less than what they deserved: the five acres of parkland which they would turn into exquisite gardens to surround the grand house with a landscape to match it in size and manner—this had always been owed to them. They were a couple whom people referred to as ‘handsome’ and it suited them because they resonated good breeding and all that went with it: high birth, property, education, bloodlines you could trace back to royalty. They were handsome and they knew it to be true, and theirs was a world that rewarded such things. David and Margaret Blackford were exactly where they were meant to be—at the dead end of a pri

vate lane you could drive by without noticing because the newer, smaller houses of the neighbourhood acted like a palisade of brick and mortar to keep the riff-raff out. The lane’s three big houses were dealt in along the cliff’s edge, a vestige from a time when it had all been fields and the founding families of that region had built their houses on the escarpment’s very brow. This view had always been worth braving the winter gales that howled up off the lake and even then, in the early century, the occupants knew the defensible value of a horizon.

At the lane’s entrance, where it met the ordinary street, was a bulging masonry wall behind which was a cloistered convent: a rundown mysterious place their father forbade them from entering. Even the name of the convent terrified: Sisters of the Precious Blood. Their father, who rarely noticed what his girls whispered about and even more rarely took an interest in it, had—with that single restriction—made the place irresistible. In the years to come, one of the nuns would take daily walks up and down the lane from the convent to the family’s driveway and back again, having taken a vow of silence and contemplation. And the girls would tempt her, with their father’s encouragement, because he saw the nun’s appearance at his property line for what it was: a trespass. They would lounge near the gate on their bicycles and then speed out to intercept, shouting hellos, riding circles, going no-hands, skidding their tires, trying to get her to respond. Doing everything short of touching her as she walked in an eddy of robes like a villain from a comic book, her presence making the vampire crypts and legions of undead seem more likely than ever. And when the sun would go down the girls would scramble to shut their bedroom windows, even on the hottest nights, afraid she’d come for them. As if she were the greatest threat to their security, their little paradise. The only person they had to fear.

Their driveway, where the nun turned, was defined by two stone pillars which were knocked over regularly by the garbage truck and snowplow. The drivers piled the wreckage back up at new and eccentric angles in a sneering indictment of this fancy house with its crude gateposts that deserved to be bulldozed because maybe then the rich bastards would put up something appropriate, like electric gates with a keypad to come and go. A code they’d have to be trusted with. It was only the cases of beer at Christmastime—put out on the porch steps to freeze overnight—that stopped them from leaving the blocks where they fell. Instead of a metal gate, the girls’ father used an old sawhorse to block the property’s entrance from the regular snoopers who liked to just barely roll their cars along the lane and down the long drive as though this were their right—to take in the acres of gardens and the orchestrated countryside at a crawl, stopping to exclaim over new blooms or a shrub’s lush foliage when their selfsame shrub back at their modest home was still bare. As if that was treason. Just another betrayal to add to their list of grievances against these upstarts who took and kept everything for themselves. The gawkers would stop at the house and look around contemptuously before turning to inch back out, trawling for every shred of evidence to justify their position that here, without question, was the rot underpinning the nation’s decay.

The girls’ father believed that the simple wooden sawhorse he placed at the gate, with his own hands, was a denial of that judgment that wealth begat indolence because there was something practical and self-reliant about that barrier. And it fit perfectly, he would say, with the Georgian style of the house which echoed gentle country living and turnstiles, fox hunts and steeplechases, noblesse oblige, even though (their mother would remark) this was Hamilton, Canada—a town founded in the monstrous flickering shadows of the steel mills on the southern shore of Lake Ontario. A place where at night, deep in the east end, you could see the climbing flames firing the stack that spewed soot onto the narrow red brick houses in the adjacent streets, coating them, Blakean. This was Hamilton, a workers’ town.

They were sisters: Georgina, Jacqueline and Philippa. Adults now, and with families of their own, but the youngest, Pippa, was sick. Eight months pregnant with her fifth, she’d left her husband and four children in New Zealand and was coming here. The others were coming home too. More than three decades had passed since they’d run through the house on that first day, and there’d been days—too many to count—when the house had sat hard and unloved within its ruffle of green grass and hedge and flower. When the sky was dull and grey and the windows reflected bleakness, all flat and giving nothing back, and it seemed a place of such uncompromising severity that its stone walls would let nothing in or out. And then some mornings, it would rise with the sun and display the warmth inherent in its blocks and the glass would gleam and the garden, that lush profusion, would reflect inward to the rooms and fill the house with life. Figures would move from window to window as though it were a dance and they partnered with the air. And it was on those days that the world was right and days were measured in increments of joy. It was all there was and would ever be. It was family.

2

No one could see David back there in the tangle of rose bushes and if it hadn’t been for the fact of the roses themselves, and all the money and time that had gone into raising them, he would have pissed right where he was. Total privacy. Instead, he went back to the far corner under the oak where they piled small trimmings and windfall and other incidental cleanups to decompose. It was his usual spot—adding his own waste to that of the garden.

Urinating outside was, he supposed, a harmless predilection of his, and the older he got the more enjoyable it became. He unzipped his shorts and pulled his penis out just enough not to wet himself, and watched the sputtering arc splash against the leaves of the dead hosta he’d put there the day before. Relief as his bladder emptied. Not everyone ends up pissing themselves, he thought proudly. He practised stopping and restarting the stream of urine. No trouble at all. He shook himself off, zipped his shorts back up … but something didn’t seem right. What was it? and then he realized. It was the sound of liquid splashing nearby. But not from him. And then he saw. His neighbour, in the small house that abutted the back end of David’s property, was rinsing out a cooler with a hose. The man was barefoot and bare chested and wearing track pants, and with his long, unkempt hair it was no wonder he was out of work. No legitimate employer would want to look at that every day. The rhododendrons had grown up high enough along the back fence that there was a chance the neighbour hadn’t seen and that David could just melt away back to the roses without being noticed, but when he moved the man looked up and grinned right at him through the branches. No embarrassment, just a look that said Yeah, mate. Who’s the lout now, eh? Was that a thumbs-up he was giving him? David thought he read an invitation to come by for a beer, as if all it took was an act of public nudity to put them on a level playing field. As if David, with that single indiscretion, had reduced himself to a layabout with nothing better to do than ready a cooler for another case of beer. As if semi-retirement and uselessness were one and the same and they were in it together, a band of brothers arrayed against the collective indignity of being home instead of out there, on the battlefield, among men.

Fucker, David muttered.

That helped. Made him feel dangerous again. Made him feel he was stalking something, like a leopard slinking through the undergrowth. Yes, David thought. He was a leopard. Fast and sleek and vicious, and whatever crossed him, he’d crush and digest it and shit it back out. Amend the soil.

Fucking cunt, he swore a little louder. Moving away, returning to the roses now that he’d made his point. Now that he was invincible again, had marked his territory, had staked his claim. Now that he was out of reach. And how easily then the man was forgotten and became something, a mild irritation, just back there in the foliage. A half-formed rumour from beyond the known world; David back in his realm again. More than enough here, he thought, to concern myself with. The garden not the least of it.

The rose bed—David stared down at it dejectedly—was full of weeds again. He’d mulched the whole thing at the beginning of the summer but he should h

ave insisted on weed cloth when they’d first been planted thirty-five years ago. He thought about this every time he worked out there because every time he stooped and got close to the ground, like he did now, he saw the vast legions of invading dock and chickweed, even dandelion, making inroads everywhere. He’d never get it sorted before the garden tour, which was only two days away. The best he could manage, he decided, was to weed the first twelve inches in from the edge and trust that no one looked beyond that. Fortunately, the roses had been mostly finished for a month, so David knew that would be in his favour. Not many people, he thought, will stop to consider the few hundred straggling blooms that were left; not when there were so many other beds rife with colour. This will become, he reasoned, a sort of passageway they’ll use between spectacles. A place of undeniable beauty, yes—who could argue with that—but not somewhere to linger. Rather, somewhere to build your strength back up before the next marvel knocks you flat again. David liked to think of these grounds as an enormous series of interconnecting rooms with such wealth on display that it rivalled the Winter Palace—but was of course better, because it had none of the baroque gaudiness he found so undignified. And, it was his.

He knew his wife had reservations about the timing of this tour but he was the one who worked the garden now, not her, and he knew there was still much to excite a group of enthusiasts. There was the huge circular garden in front of the house with its embroidery parterre in colour combinations so vibrant and varied that it looked, truly, like the work of a hundred hands and a thousand lengths of thread, the intricate gravel paths between the beds like seams joining them together. All told, it was ninety feet across and still fully in bloom. The white garden off the terrace was still blanketed with flowers, and the shaded woodland areas were broken by patches of sunlight revealing late gentians and trefoils mixed with asters, daisies and ladies’ tresses—and even some wildflowers the birds had seeded, which David hadn’t noticed until that morning. Pale blues like the sky—something else the garden had gifted him. There was the topiary, of course, and the cutting garden and herbaceous border, and there were still masses of rhododendrons and azaleas blooming to set off the wintergreen and ferns and primulas they were planted among. Every turn, David thought triumphantly, will bring a surprise. Too many for even him to count. If only his wife were as attentive as he was, she’d see that too and stop meddling. If only she minded better.

Summer Cannibals

Summer Cannibals